Formerly the Thinking Catholic Strategic Center

Confirming Culture=Religion+Politics

The Byzantine 4th Crusade

Vic Biorseth, https://www.catholicamericanthinker.com

The Byzantine 4th Crusade is widely recognized today as one of history's most unmitigated disasters, in terms of what was planned and intended versus what was accomplished. The tangled story of the Byzantine Fourth Crusade is so full of sub-plots, political and financial crises and pressures and hidden, ulterior motives that the original intent of the whole enterprise just got lost, and left in the dust, as the “Leaders” were ever increasingly passively reacting to events rather than proactively causing them. Or, in some cases, there was, quite possibly, hidden evil intent on the part of some of the leading characters right from the beginning.

Today, we cringe at the very thought of a Christian host besieging, sacking and burning a Christian city; but most of us are unfamiliar with the culture of the era, and even the then existing precedence of similar events. Raising a great host or army, in those days, was a relatively rare and quite expensive undertaking. Once the host was assembled, before using it for its original purpose, the nobleman who raised it would always immediately use it, first, to settle accounts with all subservient or vassal entities who might be in arrears in rents, taxes or tribute, in order to help pay, feed and sustain the host on its intended campaign. In addition, in accordance with custom or unwritten law, all castles, walled towns and city-states in the path of the host would generally send out emissaries to offer support, in the form of fodder for the animals, cattle or other animals for food, water, and even sometimes tribute, in order to keep the host from “foraging” too broadly to feed itself as it marched along. Sometimes they even sent guides to aid the host in getting through and beyond the territory as quickly and uneventfully as possible. The mere appearance of a large host would be sufficient to get open offers of support for the march.

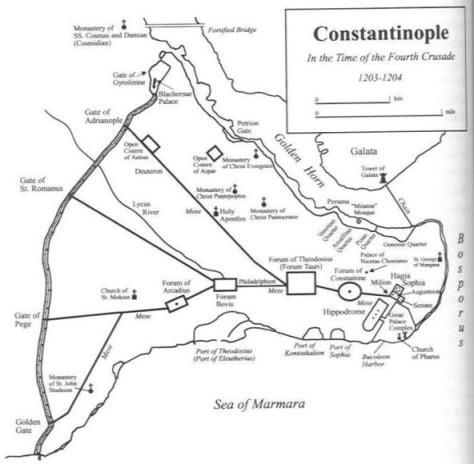

As a precedent for the Byzantine 4th Crusade, most today are unaware of the historical fact that Constantinople, although it had never fallen to a foreign invader, it had often surrendered to a rival emperor, usually after only a brief or token assault, in the imperial ascensions of 610, 743, 963, 1057, 1078 and 1081. Had it not been for the military brilliance of Conrad of Montferrat, that would have been the case in 1187. Alexius I Comnenus succeeded in an armed coup in 1081 using a foreign army, and he even allowed the customary three-days of sacking the city, which was the then expected payment of the host from any city that offered military resistance to the host, and required fighting. So, Constantinople had already been sacked, by one of its own emperors. In the history of Constantinople, most usually, all a claimant to the throne had to do was show up at the gates with a large host, and the negotiations would begin. With this in mind, it is somewhat easier to imagine how, once this Crusade was diverted into becoming the Byzantine 4th Crusade, it might have expected to just show up at the gates and be welcomed, perhaps after the briefest of skirmishes and the weakest of resistances.

As another point of historical fact, before this particular effort even began, the very notion of “The Crusades” to free the Holy Land had been defeated on the Horns of Hattin, as shown in The Medieval Crusades page. Later events would show that that event was fatal to the larger cause, and the whole effort was already doomed to failure. Be all that as it may, this particular Crusade couldn’t have been scripted any better in Hollywood, or Disneyland; it’s a story so fantastic as to be hard to believe.

By the time of the Byzantine 4th Crusade the Latin Church and Western culture had a developed doctrine of the Crusade. The Germanic and other barbarian tribes threatening the Roman Empire contributed to Augustine’s development of his Just War theory. The disintegration of the Carolingian Empire and the onslaught of Viking, Magyar, Moslems and others lead Latin Europe, not long removed from its own barbaric roots, to assert the virtues of Holy War fought in defense of the Church and the defense of existing cultural and civic establishment. In more recent history the experience of the medieval Crusade had merged the idea of the pilgrimage into the doctrine.

Pilgrimage meant the undertaking of a journey by a penitent to sacred shrines for religious benefit. Originally, pilgrims went unarmed, and as late as 1065 in the Levant some even refused to defend their own lives with arms. Pope Gregory VII sanctified the armed pilgrimage, and transformed the meaning of militia Christi from the figurative to the literal interpretation. It had previously referred to monastic asceticism; under Gregory, it was expanded to include military combat. All of this stemmed from the religious and cultural importance given the religious pilgrimage.

When the first medieval Crusade set out from Europe the doctrine was not yet fully formed, but by the time of the Byzantine 4th Crusade it had developed, and the canonists had elaborated a specific doctrine for the Crusade, which could be summoned or authorized by the pope, with a specific goal, for a specific period and against a specific enemy.

The Taking of the Cross, for the order and action that was to become the Byzantine 4th Crusade, was first preached in 1198 by the new pope, Innocent III, who was acutely aware of his responsibility as the leader of Christendom, and of the failures of the Crusades thus far in the deliverance of Jerusalem. The call was aimed at towns, counts, dukes and barons, who should provide Crusaders for a period of two years at their own expense. Kings were specifically not mentioned, because Innocent intended the new Crusade to be more under papal control than it would be if any King was involved.

According to their resources, the towns and nobility were to supply men and/or money for the cause. Both pilgrims and contributors were offered indulgences for the remission of sins, and those who put on the Cross would receive protection of their goods and property, and a moratorium on the interest of any debt. Bishops were also asked to give of money and/or men. Collection chests were set up in Churches everywhere to collect the donations of the masses.

But the call largely fell on deaf ears, for Western culture was distracted by troubled times in the feudal societies of Christendom.

The civil distractions adversely affecting the timely launching of the Byzantine 4th Crusade involved war and political instability. England and France were in a continuous on-and-off state of war, since Richard Lion Heart returned from captivity in 1194. Count Baldwin of Flanders was at loggerheads with his own French suzerain, the French King Phillip Augustus. Two of the West’s greatest maritime powers, Genoa and Pisa, were at war with each other. Philip of Swabia, allied with France, and Otto of Brunswick, allied with England, represented two rival claimants to the imperial crown of Germany. The boy-King Frederick and his mother Constance were fighting to maintain Hohenstaufen rule in Sicily. Pope Innocent, continuing his predecessor’s work to stabilize Western culture and end feuds and wars, used the very real (in his eyes) need of the Byzantine 4th Crusade to unite contentious Western powers against a common enemy.

Innocent was bitterly disappointed when the date called for passed with no response to his call. He levied a papal tax on clergy to increase funding for the enterprise, and continued to preach the Crusade, in increasingly strong terms.

The first to heed the call were the commoners who were motivated by the preaching of a charismatic priest named Fulk, of Neuilly, at a country Church near Paris. His fame began because he preached in Church and in public strong sermons about the two major vices of usury and lechery. He pointed out, in public, the worst example sinners in these vices, including even other priests and their concubines. He was credited with “saving:” numbers of concubines and prostitutes from lives of sin, either recruiting them into orders of nuns, or finding for them dowries and husbands.

How Fulk came to be so motivated to preach the Byzantine 4th Crusade is not clear, but once he started, his popularity, fame, rhetoric and charisma moved many to put on the Cross. He traveled broadly, preaching everywhere. He became a zealot in the cause, and recruited monks to preach the Crusade for the pope. Although he did enlist a few nobles, Fulk was noted to have personally bestowed the Cross of the Crusade on literally thousands of commoners. Which was troublesome to some, because it harkened back to the horrors of the likes of Peter the Hermit and similar past “leaders,” who motivated and led unruly mobs of ill-prepared commoners to their own eventual slaughter. These were not trained and disciplined fighting men; in military parlance, they were rabble, easily confused, quick to panic and likely to break ranks under pressure.

But most of those moved by Fulk to take up the Cross seem to have been rather lightly motivated, for they did not follow through. In the heat of the moment, under the spell of fiery rhetoric, they enthusiastically responded. However, like the seeds cast in shallow soil, the commitment did not take good root, and soon withered in the light of worldliness and reality.

The first nobles, in serious numbers, to heed the call for the Byzantine 4th Crusade were all participating in a tournament, of all things. A full 15 months after Innocent had called for the Crusade, and six months after the date it was supposed to depart, Count Thibaut of Champagne held a tournament at his castle at Ecry-sur-Aisne in the Ardennes region of northern France. Popular legend, not backed up by any real history, places Fulk there preaching to the Nights. History does not record what happened there to recruit the Nights, but whatever it was, it was probably fairly dramatic.

Medieval tournaments were comprised of competitive matches using the martial arts of the era, exercising the precise skills that would be required of participants of the Byzantine 4th Crusade. Nobles and Nights from far and wide gathered to test military prowess, to display honor, to impress the ladies, and to enjoy the heraldry, pageantry, feasting and social amenities of their high class. While all gentlemen – meaning all noblemen and Nights – were highly skilled with weapons, having been born to it, and having been continuously trained in combat since very early childhood, it is unlikely that they were any more or any less pious or religious than the commoners in their domains. It seems unlikely that these men were moved solely by religious zeal to take up the Cross, although some may have been, and religious piety certainly affected them all. Christian piety ran much, much deeper through all levels of society then than it does today.

But one characteristic of this class made them less likely to drop the Cross, once having donned it. And that one thing was all bound up in the code of Chivalry, and the associated personal sense of honor. Once a Gentleman - noble or a Night - gave his word on something in the presence of others, especially the ladies, he was honor-bound to keep it. If they had second thoughts after taking up the Cross, as so many of the commoners had, they could not so easily put it aside and forget it. To do so would be to bring disgrace upon them. At this tournament of champions, we might not know what the original motivation was, but we know that, based on what they all swore, one after the other, that the Byzantine 4th Crusades was definitely On.

The initial wave of enlistments for the Byzantine 4th Crusade that came out of the tournament at Ecry or shortly thereafter included about a hundred “companies” of about a hundred men each. Most were commoners. The usual proportions for medieval armies were approximately one heavily armored and equipped nobleman or Night to two lighter armed and equipped mounted squires or sergeants, and about four to six foot soldiers, or sergeants on foot. All of these were highly skilled fighting men, committed to backing up their leader. This support included everything from carrying and maintaining his armor and weapons to actual combat in his support. The typical gentleman’s entourage often included one or more carts or wagons for weaponry, armor, tents, water and provisions. When gathered into a great host, the champions (gentlemen) would comprise the “heavy horse,” the mounted squires made up (or led) the light cavalry, and the sergeants on foot comprised (or led) the infantry.

Noblemen, of course, normally resided in large castles or fortified palaces. Lesser nobles resided in fortified manner-houses or smaller castles. Nights generally resided in towers or lesser fortifications within the domain of their suzerain. All were not equal; a poor Night might have only one squire, with no (or one or two) other assistants; a prosperous Night might have multiple squires and a large entourage of various assistants. All Nights were generally expected to hold and defend some part of the domain in vassalage to their suzerain, to be prepared to sally forth against any intruders, and to generally respond favorably to calls to action.

In the great effort that would become the Byzantine 4th Crusade the early leaders were the Counts Thibaut of Champagne, Louis of Blois and Baldwin of Flanders. While they set about the business of raising an army, they sent ambassadors, including Geoffrey of Villehardouin, the Marshal of Flanders, to find and negotiate transportation by sea. France had no port with the capability of building or obtaining the ships for such a major enterprise. Pisa and Genoa were somewhat depleted and exhausted from their war with each other, and the envoys representing the Byzantine 4th Crusade thus wound up in Venice.

These envoys carried with them the full authority to bind the nobles who sent them to contracts not yet written, and they were fully authorized to go anywhere, and to negotiate significant contracts with anyone. The trust thus placed in these men by the nobles was virtually unlimited. All the details were to be worked out by them, and whatever agreements they made would be binding on the nobles. They needed a fleet to carry the great army they were raising. So, the envoys of the Byzantine 4th Crusade eventually wound up in the great port city at the head of the Adriatic, the only major sea power city-state not otherwise occupied by troubles and war.

There they met the great Enrico Dandolo, the Dodge of Venice, who was perhaps the most fascinating character in the whole story of the Byzantine 4th Crusade. No fiction writer, no Hollywood producer, no bizarre artist of any kind could possibly have invented such an incredible personage. The envoys were welcomed with the pomp and honor that befitted ambassadors of great feudal Lords.

The great Dandolo entered at the end of a huge procession, preceded by his sword, a chair-of-state draped in cloth of gold, and a parasol; he was garbed in imperial splendor. Dandolo was quite old, at least an octogenarian, and – he was absolutely blind, since some time after 1176, when we know that he still had his vision. Advanced age had done nothing to dull his mental acuity, and indeed had apparently only sharpened it, as he was increasingly recognized as an excellent strategist, tactician, diplomat and negotiator, and the possessor of a particularly penetrating sense of politics. He alone in this entire story represented what we today think of as a King; he was in practicality, although not in title, the Monarch of the City-State Republic of Venice.

Dandolo received their credentials and the letters committing the noble Principles to whatever contracts these men negotiated. He agreed to grant them an audience four days hence, an indication of how important he thought they were. Dandolo was universally respected for his benevolence and his eloquence, but he was very busy with the responsibilities of Venice. Some who wrote of the Byzantine 4th Crusade describe him as delaying the negotiations, but this seems not to be true. He was personally involved in multiple ongoing litigations and affairs of state that demanded his attention and time.

The Byzantine 4th Crusade Contract was negotiated at the audience with Dandolo. That men in those days showed more emotion, and were more emotional, than men today might be a gross understatement of the case. Apparently, when men put forth a proposal that they fervently believed in, it was generally done with the accompaniment of outbursts of open weeping. That great men of war, perhaps the greatest in the world, would put on such emotional displays was quite surprising to me, although real scholars of the era might not be surprised at all. This audience involved men falling down in tearful, emotional displays, involving refusal to get up from the spot until their request was granted.

It's hard to say how that sort of thing might play today, but then, at that time and place, it triggered similar emotional and tearful outbursts from the listeners, and quite emotional commitment to the cause.

The great cause, the Crusade for Jesus Christ and the holy places of Jerusalem, was very emotionally set forth by Geoffrey, the Marshal of Champagne, ending with a request to obtain a fleet of vessels for the mission. They requested vessels sufficient to transport 4,500 Nights, 4,500 horses, 9,000 squires and 20,000 foot soldiers. This was the original request of the envoys for the nobles of the Byzantine 4th Crusade.

As we shall see, this would turn out to be a gross over-estimation of the forces that would be raised and that would actually show up to be transported. It did not appear to be any fault of the envoys; the great feudal Lords who sent them fully intended and expected to raise a force of this size, or larger, from the outset.

Eight days later they met again and Dandolo offered to build and provide the fleet at a cost, in the currency of Cologne, of four marks per Night, four marks per horse and two marks per squire and foot soldier, for a total of ninety-four thousand marks. In addition to the requested transport, Dandolo offered to supply at the expense of Venice fifty war galleys to support the Byzantine 4th Crusade on the condition that Venice would receive a half-share in any spoils of war taken. This did not mean land; it meant plunder. Venice would also provision the Crusade for one year by sea at no further cost.

The next day, agreement was reached; all terms were as above, but the total payment was reduced to eighty five thousand marks of Cologne to be paid in four installments by April 1202, when the army of the Byzantine 4th Crusade should arrive in Venice. The fleet would be ready to sail on June 29, the feast of Saints Peter and Paul.

At that point, an important leader of the rank and power similar to that of a King began, inexorably, to get more deeply involved in an enterprise that the pope who called for it specifically intended to exclude from the control of any King. Dandolo was, in effect, the “King” of the most powerful maritime city-state in Western civilization that was not involved in a war at the time. And, as events later would prove, his personal attention and commitment would be drawn deeper and deeper into at least overseeing if not participating in the actual leadership of the Crusade as a simple matter of protecting his and Venice’s truly massive investment in it. In the best case, this Crusade would be a great windfall for Dandolo, Venice, the whole surrounding area, legions of carpenters and craftsmen, sailors and others. On the other hand, if this venture failed, or if did not otherwise pay off, it could potentially bankrupt Venice and bring about a financial/economic crisis of epic proportions. Enrico Dandolo and Venice each had a vital personal interest in the success of the Byzantine 4th Crusade.

Not counting the 50 war galleys, this bargain meant building 450 new transport ships for the fighters and mounts of the Crusade, and a concentrated effort to meet the demands of the bargain that entailed suspending all other Venetian commerce for some 18 months, just to concentrate on satisfying the needs of this one contract. Although ship-building in that era was largely a private enterprise affair, the Dodge of Venice had authority and influence enough to engage all of the private ship yards throughout the entire lagoon to concentrate on this single effort. He also began the effort of gathering the many tons of provisions needed for the venture from the entire surrounding countryside. Most difficult of all may have been the supplying of the manpower for the war galleys and the sailing crews of all of the transport ships. This likely entailed the recruitment of some 14,000 men, around half of the able-bodied seamen and fighters of Venice. It was without a doubt the largest economic undertaking in all of Venetian history.

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, a seemingly unrelated intrigue was developing. In Byzantium, the emperor Isaac was dethroned, blinded and imprisoned by his own brother, Alexius, in a palace coup that placed Alexius III on the throne in Constantinople. In Byzantium, blindness was seen to be a disqualification for rule. Isaac’s youthful son, also named Alexius, who, with his father, promised to not plot against the throne, was not blinded and was allowed relative freedom of the palace and court, although he was carefully watched by the new emperor Alexius. In a daring escape, he cut his long hair, donned Western apparel and mingled with the foreigners on a ship bound out of Byzantium. He was not recognized by searchers as the deposed Prince, son of Isaac, and was able to make his escape. The young Alexius managed to contact his sister Irene of Germany and obtain armed escort and safe passage to the court at Hagenau.

These events were unfolding as Geoffrey of Villehardouin, the Marshal of Champagne was returning to the great Lords with news of the contract executed with the Doge of Venice regarding transport of the great Crusade to the Levant. They found the Count Thibaut of Champaign quite ill and bed-ridden. He knew he was dieing, and he settled his affairs and made out a will. Although he roused himself from bed when he heard the good news, he soon returned to his bed, and in short order, he died. Since he had been more or less assumed to be the over-all leader of this Crusade, in so much as there could be such a leader among co-equal, independent-minded feudal lords, this called for a great council to determine who would take his place. The determination of the remaining lords fell to Boniface, Marquis of Montferrat, and Geoffrey was sent to offer him the post, the men and treasure Count Thibaut had willed to the leader of the Crusade.

We must here recognize that any title or rank accepted by any feudal lord or even King that sounded like overall command was not the same as it would be today. There was at that time no such thing as the unity of command that today’s military men would recognize. A lord could not even be certain that his own vassals, and their men, let alone any other lord, would all unhesitatingly follow his every command in every circumstance. A Crusading host comprised of many separate noblemen and their retinues would be more akin to several large cattle drives all headed in the same general direction, as compared to a modern day large army/navy/air force with a single mission. Generally, exact orders regarding destination, timing, battle plans and so forth would be so general as to be almost non-existent, at the level of the common fighting man. The reasons were that, many men, if they knew where they were going or what they were doing ahead of time, would simply change course and not follow the course laid out for them. The lords themselves would be given vague and unspecific instructions by the “leader,” and the farther down the line the orders trickled, the vaguer they would become. In those days, mass-desertion could be a greater drain on manpower than battle itself.

Boniface Marquis of Montferrat was held in high esteem by virtually everyone. He even acted as emissary between the feuding factions of the house of Hohenstaufen and the house of Welf for the German Empire, and was trusted by both sides. He was indeed a vassal of Phillip of Swabia, a Hohenstaufen, yet he acted as go-between on behalf of the Pope for Otto, whom the papacy favored, while seeking truce if not peace between the two factions. When he received the Crusade leadership invitation from Geoffrey, he first went, as a matter of protocol and honor, to Phillip Augustus, King of France. He then met with the other Crusade nobles at Soissons, in an orchard adjoining the Benedictine abbey of Notre Dame.

At Soissons the crusading barons, on their knees, offered the Lombard Boniface, Marquis of Montferrat, command of the host, and all the treasure left by Thibaut for the Crusade, and all the fighting men who had been vassals of Thibaut. As had happened at the negotiations in Venice, there were great emotional demonstrations and outbursts by great men. Boniface himself very emotionally fell to his knees before the other nobles and Nights, and irrevocably committed himself to the cause of the Crusade. They all moved into the abbey church of Notre Dame to solemnize the proceedings. Nivelon, the bishop of Soissons, along with the two Cisterian abbots and the now famous preacher Fulk of Neuilly, fastened the cross on the shoulder of the Marquis of Montferrat. The day after he took the cross, Boniface left to settle his affairs.

His return to Montferrat was not direct, however. He first spent some time at the great abbey of Citeaux in the Burgundian wilderness, for the “general chapter” meeting of the white monks on September 13, the eve of the Exaltation of the Cross. The white monks had been very involved in preceding Crusades, and many other nobles and Nights were in attendance. Boniface recruited some of them to his cause, and in particular, obtained permission for the company of Abbot Peter of Locedio, for his good counsel. Boniface then paid a visit to his own lord (and cousin) Phillip of Swabia, at the court of the German King at Hagenau. They were on good terms with each other, and Boniface sought support, in whatever form he could get it, for his new cause. Boniface had visited Phillip as an envoy of the pope in an attempt to settle the dispute over the German throne, and, he had represented the Hohenstaufen cause in Paris to Phillip Augustus, King of France. Because of the ongoing dispute between Hohenstaufen and Welf, it was unlikely that Boniface could recruit many, or even any, of the barons of Germany, since things were so unsettled at home. Yet, he was duty bound to try.

It was at Hagenau that Boniface encountered the unexpected guest, the young refugee Byzantine prince Alexius, son of the recently deposed and blinded emperor Isaac II Angelus. They were distantly related. Alexius’ sister, Irene, was the wife of Phillip of Swabia, King of Germany and Boniface’s suzerain. Boniface’s brother Conrad had saved Alexius’s father’s reign with his military skill. Conrad had later been cheated of his reward, and another brother, Renier, had been poisoned in another Byzantine political intrigue and plot in Constantinople. The young Alexius began trying to persuade Boniface of Montferrat, brother of Conrad and Renier, to come to the aid of his father Isaac, and to help him depose the current emperor Alexius III, and to help the young prince Alexius himself to ascend the throne in Constantinople. But the single minded intent of Boniface was fastened on the oath he had taken. The Crusade would have to come first. But the young Alexius, perhaps seeing in Boniface his last, best hope, however uncertain, of regaining his inheritance and the throne, began to fasten himself to Boniface.

Prince Alexius had visited the pope and returned before Boniface arrived at Hagenau. There he petitioned the Holy See to help “return” him to power in Constantinople, but the pope was not inclined to do so. In so far as the papacy was concerned, Alexius III had as much entitlement to the throne as his brother Isaac II, but the claim of the young prince Alexius to the throne was weaker, and considerably less convincing. The prince had been born before the ascension of his father Isaac to the throne, not after, and he was not viewed to be any sort of automatic heir to it. The prince returned to Hagenau without the support of the papacy. Later, after meeting the young prince at Hagenau, Boniface of Montferrat also visited the pope, and, one of the several things they discussed was the request of prince Alexius to Boniface for aid in “rescuing” the throne at Constantinople from his uncle. By this time, Innocent was somewhat vexed by the very idea, now put before him a second time, and he strongly rejected it, and Boniface obediently agreed to pursue the original goal of freeing the Levant from the Moslems, and not detouring toward or campaigning against any Christian city.

The papal prohibition did contain an escape clause, in that the Crusade could not be diverted from its sworn mission, and could not militarily engage any Christian city without due cause, or, unless necessary. It might become necessary if some Christian entity openly opposed the Crusade, or somehow hindered or prevented the progress of the host toward its sworn goal.

Boniface then went to Lerici, a small town between the warring cities of Genoa and Pisa, attempting to mediate a peace between them, acting as a mediator for pope Innocent. The Marquis then returned to Montferrat to make his own personal preparations for departure on the venture that was to become the Byzantine 4th Crusade.

A point to remember in all of this is that the proposal of the young prince Alexius, now rejected by Phillip of Swabia, despite the passionate support of it by his wife Irene, Alexius’ sister, and now rejected by the Marquis of Montferrat, and rejected by pope Innocent, is that is was less a plea for armed siege and assault as it was for an armed “show of force” for an assumed palace coup, with an assumed rally of support for Alexius and his father Isaac from within the walls of Constantinople. It had happened before, and it was the sort of plea that would not necessarily be rejected out-of-hand by most gentlemen of that day. It might not take utmost priority, but neither would it be summarily dismissed. It was, however, fraught with danger, in that it could quickly escalate into a great battle against the strongest Christian bastion on earth, at that time. Constantinople had never fallen to any foreign invader, for many, many centuries, and many invading armies had been broken on her walls. That had happened before, too.

It was soon becoming apparent that the numbers of those who had taken on the Cross were falling far short of the contracted-for numbers. It was recognized even at the initial gathering places in various originating domains, was further confirmed as the Crusaders marched and joined those of other domains, and at virtually every encampment or gathering point. Each lord was dismayed at the turnout of his own vassals, and then was further dismayed as he encountered other lords and compared notes. Many traveled through Montferrat and paid their respects to the Marquis, and the numbers were, always, down.

Now, while the details of where the Crusade was first bound – Egypt - were not widely known, the nature of the contract and rough estimates of the overall cost of it were widely known, by the nobles, Nights and the host. No one was yet concerned about the cost figures. But, those who had taken the Cross, particularly those of lower rank, fully expected the Crusade to be heading directly to the Holy Land, perhaps even to Jerusalem herself. The high level decision to go to Egypt involved the timing of an existing and not expired truce between the King Aimery II and the Moslems, and the strategic idea of taking Alexandria first and closing the “back door” of Moslem reinforcement of the Levant from Africa. The Crusade could then enter the Holy Land from a position of strength. If the rank and file of the host had known of the first sailing destination and the first battle plan targeting Egypt, many of them might have simply either deserted the cause, or set out on their own separated from the main body bound for Venice. In fact, rumors of the plan for Egypt may well have contributed to the numbers who left for the Levant on their own, rather than with the host gathering in Venice. Scattered rumors of the planned Egyptian campaign slowly began to percolate through the host.

The great Crusade cost factor was of great interest to me, because it highlights the faithful naiveté of the nobles of the era. The effort that would become the Byzantine 4th Crusade, like all other Crusades, would be paid for by the participants – those who had taken upon themselves the Cross. They all knew that. However, the leading nobles alone had legally bound themselves to the terms of the contract for transport with Venice, and they alone would be held accountable for those terms. Disregarding the purely legal aspects of the contract, they were so heavily honor bound to honor it as to be very nearly enslaved to it. Each member of the host who arrived in Venice with his lord would, of course, pay his agreed share to his lord, if he hadn’t already done so ahead of time. But there were many lesser nobles and “poor” Knights who paid little, and most of the commoners in the host paid very little or nothing at all, other than their own very risky physical contribution to the Crusade.

As it became increasingly apparent to all Nobles that the numbers were severely down, many hesitated, and even began to seek alternate routes to the Levant. Some sought to avoid the potential ugliness of being part of a weakened and virtually impoverished host making its way as best it could to the Holy Land. Or, worse, unable at all to keep their vows of the Cross, and forced by circumstance to return home in disgrace.

Collection chests from monasteries and churches for the cause were frequently divided up, sometimes by high ranking clerics and sometimes by the pope himself, between the lords leading the specific Crusade, and the various lords and orders currently under duress in the Levant itself; these funds were mostly viewed as intended for the overall great cause, thought of as “The Crusade,” rather than the current individual Crusade being organized. Thus, most of these funds went directly to the Holy Land, and were of little benefit to the satisfaction of the Venetian contract.

Every prominent Crusader had a certain amount of autonomy, his own goals and plans, and felt bound to the larger host only insofar as the larger host served his purposes. This was also true, although to a lesser extent, even of the common people who took the Cross. This presents a situation that would be intolerable, even unthinkable, to modern military commanders. Be that as it may, many nobles and their vassals, and many Nights and their entourages, for various reasons, sought their own transport to the Levant, other than by way of Venice. Several hundred Nights, who should have been part of this Crusade, found their way to Palestine in their own way, usually sailing from other smaller ports. Going by the usual proportion of men to Nights, this may reasonably be estimated to have included more than two thousand fighting men. While this was not enough to make a real difference in the critical situation developing in Venice, it didn’t help it either.

Renaud of Dampierre, the Night who had been entrusted with the duty of fulfilling the Crusading vow of the dieing Count Thibaut of Champaign, was one of these. Heading straight for Antioch, he was ambushed by the Moslems, and his entire band of some eighty Nights was wiped out. Only one Night escaped; Renaud himself was captured and would remain in Moslem captivity for some thirty years. Some failed to show at Venice due to other factors. John of Nesle, leading perhaps as much of half of the force of Count Baldwin’s force from Flanders, set out by ship, only to encounter difficult sailing. All summer long they struggled against contrary winds before passing through the Straights of Gibraltar. They burned and sacked an unnamed Moslem port on the Mediterranean, and decided to take to port in Versailles for the winter.

Those who arrived at Venice, always in disappointing numbers, traveled by the customary route via the Mont Cenis Pass and Lombardy, with stops at various shrines and places of piety, such as Clairvaux and Citeaux. They came from the sub alpine provinces of current day Italy, and from Flanders, Picardy, Ile-de-France, Blois, Shartres, Champagne, Burgundy and the Rhineland. There were few or no English; while King John collected a tax on lands for support of the effort, he was deeply engaged in a struggle for his throne with his nephew Arthur, who enjoyed the support of Phillip Augustus. John still managed to send one thousand marks for the effort through his nephew, Louis of Blois. King John not only did not accept the Cross himself, but placed obstacles in the path of other English enlistments. Clerics did not push the issue, for Innocent did not want any Kings involved.

Most who arrived at Venice came out of the initial wave of enthusiasm that was born of the tournament at Ecry. A more limited contingent came out of Germany, lead by Conrad of Krosigk, Bishop of Halberstadt, excommunicated by Innocent for his support of Phillip of Swabia over his rival Otto. He was seeking penitence, penance and perhaps absolution via the Crusader’s Cross. Accompanying him was Count Berthold of Katzenellenbogen, Henry of Ulmen and several other lesser German Lords.

Remember, the Treaty of Venice had not been made in the name of the whole host, but soley in the names of the Counts of Flanders, Blois and Champaign, and now the Marquis of Montferrat, who had willing accepted and taken upon himself the commitments of the deceased Thibaut of Champaign. The army, as a whole, had no corporate character and no standing as an entity in law. The cost of transportation was, as always, the burden of each individual Crusader; they all paid their own way, and helped each other out as best they could. This meant, sometimes, foraging, as well as looting of any enemies encountered.

During this period, before the host was fully gathered in Venice, the popular preacher of the Crusade, Fulk of Neully passed away, causing much grief and a general lowering of moral, for it was seen to be a bad omen on the eve of the great Crusade. Fulk had gathered possibly the largest amount of treasure for the cause, but very little of it would be available for the payment due to Venice. Much of it was already spent, and more willed, by Fulk for the support and transportation expenses of many poor Crusaders; thousands of them. Much more had already been sent to the Holy Land, where it was largely used to do needed repairs to fortifications and living facilities after a devastating earthquake. Huge amounts were spent in this fashion in the repair of the walls of Acre, Tyre and Beirut.

Venice, for her part, had fulfilled her obligations to the Treaty fully and completely. All the ships were built, rigged, crewed and ready to sail. All provisions had been gathered and loaded aboard. Fifty war galleys stood ready, provisioned and manned, to support the effort. Venice had literally stopped all other commercial activity throughout the entire area just to enable the completion of all the work, provisioning, recruitment and training needed to satisfy the contracted requirements. Most importantly, there had been no income for anyone in the area for fully a year and a half, in anticipation of payment from the great Crusading host for all this effort. This put just about all ordinary citizens and businessmen of Venice in near desperate financial straights.

Despite the theories of some historians, at least up to this point in the story, the evidence shows that there was no diabolical plot to divert the Crusade to Constantinople, by the Venetian Dodge Enrico Dandolo, or by Boniface, Marquis of Montferrat, or anyone else, the continuous hopes and prayers of the young prince Alexius notwithstanding.

As elements of the Crusade slowly straggled into Venice, they were directed to the Island of Saint Nicholas (the Lido) in the lagoon, where their pre-embarkation encampment was established. All the Venetian ships for the Crusade, about 500 of them, rested at anchor off of the Lido. The Venetians and their Dodge grew increasingly alarmed as the stream of fighters never seemed to hit the expected crest, and then slowly began to peter out, with such clear and obvious low numbers as to ensure that the entire expected 33,000-plus figure would not be met. Ultimately, the numbers amounted to around a third of the expected, and contracted for, numbers. Panic began to set in.

The great Crusading lords had each brought with them sufficient funds from their own domains only, fully expecting other lords, in sufficient numbers, to join them in the cause. They had all acted in good faith. They had settled their personal affairs, including putting heirs or temporary rulers in charge of their domains, made collections and even sold some lands to raise funds for the Venetian Treaty before departing for the encampment on the Lido. As the departure date approached and then passed with the numbers still far below expectations, with all those contracted-for ships standing there at anchor, the specter of dishonor began to rise before them all.

On the Venetian side, the aged, blind, but wise and charismatic Dodge Enrico Dandolo was no king, although he enjoyed almost king-like respect and veneration from the Venetians. He had a ducal council and a Great Council to answer to, as well as the people of the Republic, from whom he had demanded so much, and to whom he now owed payment for services rendered. He was the one they all turned their faces toward, in full expectation of being paid their just dues in fulfillment of their many individual contracts.

In the midst of this growing quandary, cardinal Peter Capuano, the papal legate, arrived on the scene, and nearly everything he did had a negative effect on the situation. For whatever reason, he arrived late, after the date of departure for the 4th Crusade, which had passed with the host still encamped on the Lido hoping for more arrivals. He was a total stranger to the French lords and to the Venetians alike. The first thing he did was to go onto the Lido and begin sending Crusaders home; he removed the cross and the vow from the poor, the sick and the women. When the lords and the Venetians became aware of what he was doing, they were infuriated. The lords didn’t want their manpower reduced without their input, and the Venetians didn’t want the contracted-for numbers reduced even further, for payment reasons.

Once the credentials of Peter Capuano were recognized, the anger was suppressed to some degree. It appears that the French lords eventually accepted him as the papal legate, but distrusted him, and did not consult him on matters pertaining to route, destination or strategy. The Venetians did not even accept him as papal legate. They informed him that he could accompany the Crusade as a preacher, but that he would not be accepted as papal legate. His influence was thereafter considerably less than it should have been. The 2nd and 3rd Crusades had been lead and financed by kings; this one was supposed to be more under the control of the pope, and his legate was supposed to be his man on the scene and his direct representative. As Peter Capuano’s influence and importance was lessened, so was the direct influence of the pope lessened.

The cause, mission, assemblage and organization that would morph into what history would record as the Byzantine 4th Crusade was, from that point on, not controlled by anyone.

Venice, the greatest city in Latin Christendom, now faced a financial disaster. The Dodge of Venice went to talk to the barons on the Lido about the terms of the Treaty. After the meeting, Villehardoun and others recorded that the Venetians had fulfilled the contract completely. The ships all stood ready, crewed, manned and provisioned, well ahead of the date of departure. It had taken a great deal of time and treasure to build and/or purchase all of those ships for the cause. The French lords then asked the host, the great and the small, to pay more into the collective pot to satisfy the terms of the Treaty. Some of the poor Crusaders who remained despite the efforts of Peter Capuano declared that they could pay no more; the lords collected what they could from those who could pay more.

The great lords then held a council and decided to impoverish themselves rather than default on their word. It was not unanimous; only the lords who’s names were on the Treaty felt absolutely bound by it. All had already given their fair share, and most gave more, at this point. The counts of Flanders, Blois, Saint Pol, and the marquis of Montferrat, and others of their persuasion, gave everything they had, in money, and in gold and silver vessels, ornaments and other items. The host witnessed the carrying of all the vessels and treasure of the lords from the Lido across to Venice.

It was not enough. They still lacked 34,000 marks of the 85,000 originally contracted for. There were no other funds available. The situation began to get ugly, in many ways.

The Venetians were pressing Dandolo for payment, and Dandolo pressed the lords for payment. He even threatened to cut off their water supply on the Lido, although he never carried through with that threat. Today the Lido is a beautiful beach resort, but then, it was a little strip of sun-baked barren sand, blistering hot in the Italian summertime. Nothing is worse for the morale of an army than prolonged inactivity. Wild rumors were rampant, and desertion was now becoming a growing problem. Impoverished soldiers were getting food on credit, and getting new Venetian loans just to continue to eat. Venetian merchants were growing more alarmed at how much food they were sending to Lido for no real money in return.

Venetians were also growing increasingly alarmed at the presence of a large foreign army within their defenses. The Lido was an island, but transport between the island and Venice was close and easy. Some Crusaders were traveling farther and farther to find more willing merchants with whom to deal for food and establish credit. Some of these Crusader foragers never returned. Time was also becoming a crucial factor. Medieval men did not sail the seas in winter season, even in the relatively mild Mediterranean. The idle, hungry host had seen the vessels and treasures of the lords transported to Venice, and they assumed the Venetians had been paid, perhaps too much. They grumbled against the Venetians as much as the Venetians grumbled against the host.

The great lords informed the dodge of Venice that they were unable to pay any more, and Enrico Dandolo realized the truth of their words, as well as the gravity of the situation for all involved. He discussed the matter with his advisors, including the potential menace to Venice of this increasingly demoralized host festering within the defenses of Venice. No such foreign force had ever been allowed into the lagoon before this.

In discussing what to do with this foreign army, the topic of Venice’s ongoing conflict with Zara was raised. Zara was a port city of Dalmatia; it is the current city of Zadar in Croatia on the Adriatic Sea. It had been, on and off, a vassal state of Venice, changing hands repeatedly between Vassalage to Venice and to the king of Hungary. It had always been important to Venice as an Adriatic port for replenishment of the Venetian fleet, and as an important source of hard oak, for ship building. Zara stood alone in the entire region in open defiance of Venice.

As mentioned earlier, it was universally accepted in medieval Europe that a ruler had the right to stabilize his domains, quash rebels and exact oaths of loyalty before leading his newly raised army on a Crusade. This was commonly done both in the preparatory phase as the army was raised, and on the march, through or past vassal estates. Venice still considered Zara to be a vassal state, although Zara now enjoyed the protection of Bela III of Hungary, who had built a strong fortress there.

Dandolo dangled a proposition before the French lords. It consisted of using the Crusading host to help return Zara to Venetian rule in return for a temporary moratorium on the 35,000 mark debt, until it could be paid out of the Crusader’s portion of any loot to be taken in future battles. The alternative, of course, was to cancel the entire Crusade and return home in disgrace.

The lords had to confer with each other, and with the papal legate, and Dandolo had to confer with the ducal council and the Great Council; but it looked like a way to continue with the Crusade. Peter Capuano, the papal legate, accepted the proposition as a lesser evil for the sake of a greater good. He said that, while Innocent could not condone any attack on Christians, he might overlook it if the alternative was the disintegration of the entire Crusade. The papal prohibition forbade attack on Christians except in case of necessity and after consultation with the legate. There was a general agreement among the lords to sail to Zara.

Peter Capuano’s decision enervated anew the hopes of young Alexius Angelus toward somehow regaining his throne in Constantinople, perhaps through the offices of the legate. And particularly since he, once installed on the throne, could personally finance the whole of the Crusade.

There was the problem of the fact that this was almost entirely a French undertaking, with merely contracted support from Venice. The Venetians had not, necessarily, taken the cross, although some individuals may have. The port of Zara was (or had been before the last revolt) a vassal of Venice, not of any of the French lords. This problem dovetailed with another problem, that being, the ever growing Venetian interest in the success of the entire enterprise, which involved the very economic survival of Venice itself. Here, the political insight and acumen of Dandolo showed itself at its best.

The blind, old dodge took the cross. At the Mass of the Nativity of the Virgin in San Marco, filled with Crusaders and Venetians, the dodge appeared in full ceremonial garb, ascended the pulpit and addressed the congregation:

”Sirs, you are joined with the most valiant men in the world in the greatest enterprise that anyone has ever undertaken. I am old and weak and in need of rest, and my health is failing. But I see that no one knows how to govern and direct you as I do, who am your lord. If you agree that I should take the sign of the cross to protect and lead you, and that my son should remain and guard the country, I will go to live or die with you and the pilgrims.”

San Marco rang out with the cries of Venetians assenting to his request and clamoring to take up the cross themselves. The dodge descended to kneel before the altar in tears, to the cheers and tears of Crusader and Venetian alike. The Crusaders rejoiced at the crossing of the dodge, and of the new recruits joining them. Enrico Dandolo enjoyed as much personal popularity among the Crusaders as he did among the Venetians.

The news was spread that the debt was forestalled, the Crusade was on, and departure was imminent. A great celebration began on the Lido. Spirits were lifted in the whole area. The initial target of Zara was kept from the rank and file, because if they knew ahead of time that they might be re-directed against a Christian city, they might have deserted the host and either returned home as best they could, or found their way to the Levant as best they could. The position of the pope, it would turn out, was opposed to the proposition. Once he learned about it, he sent a strong letter forbidding it. Although it arrived in time, the majority of the lords chose to ignore it; the Crusade, by that time, had developed a momentum of its own.

The Imperial Refugee Alexius Angelus had been hovering nearby, in Verona, keeping close tabs on the plight of the floundering host. When it became clear that the great Crusade would sail, he sent envoys to plead his case anew to the French lords. These envoys met with a small group of the French lords and assured them of the strong support of many Byzantine magnates and lords, including all the more powerful elements of Byzantium, who longed for deliverance and hoped for the return of the young prince as emperor. Boniface, alone, had previous knowledge of this plan, which had already been twice rejected by the pope, and by Phillip of Swabia, and by himself. He held his tongue and said nothing of it to the others.

The messengers assured the nobles that if they would but sail the short distance to Constantinople and act to place Alexius Angelus on the throne, that they would be paid sufficiently to satisfy their all of their existing debt, and to finance the entire enterprise on into the Levant. It would be an easy exercise, because the prince enjoyed so much popular support from within the walls of Constantinople. The proposition was received in a positive light, although all of the lords were not present, and when some were later informed of it, they opposed it. It was decided to send envoys to Phillip of Swabia and to the pope to present the idea. Boniface said nothing.

On the eve of sailing to Zara, the envoys left for Hagenau and for Rome. Boniface accompanied those bound for Rome, with his close advisor, Abbot Peter of Locedo, who had enjoyed pope Innocent’s close confidence for many years. Bonniface hoped to avoid the action at Zara, and planned to rejoin the Crusade afterward, wherever it might sail again. He had no taste for attacking a Christian city. He must have had some foreboding about the reaction of Innocent to the issue of Constantinople, now being raised before him a third time. Yet, he now may have hoped that the support of the other French lords and the severe financial crisis might soften the negative position of the pope. He might have hoped to just stand in the background while others pleaded the case.

The arrival of Boniface’s party before Innocent was preceded by that of cardinal Peter Capuano, the papal legate to the great Crusade. He informed Innocent of the plan to attack Zara, the crossing of the dodge of Venice, the refusal to accept Capuano as the papal legate, and the proposition to install Prince Alexius Angelus on the throne in Constantinople. Innocent immediately sent the letter forbidding the attack on Zara. Capuano was to remain in Rome, but not in disgrace; he remained the papal legate, but Innocent would not be ordered by anyone to appoint another legate. The Crusade would need to communicate with Capuano from a distance, because Capuano and Innocent alike would not suffer the indignity of the papal legate not being recognized on the scene.

The topic of Constantinople, now being raised a third time, infuriated Innocent. Innocent sent his letter, opposing Capuano’s position regarding Zara and threatening religious sanctions against any Crusader who attacked Christians, in the hands of Abbot Peter of Locedo. It would not arrive before the host stood before the gates of Zara. The notion of the Crusade being diverted to Constantinople was immediately dispensed with; Innocent remained adamantly opposed to it.

The fleet embarked from Venice with great pomp and circumstance, with trumpeting and drum rolls, and great spectacle. Dandolo sat in sartorial splendor in his great ship, which was painted imperial purple, sitting beneath a purple canopy on the high castle. Ship’s sides and castles were lined with the shields of the nobles and Nights aboard, all shining and fresh painted and making a splendid show. About two hundred forty of the available five hundred ships were actually sailing. Boniface was absent, on the thin excuse that he had other business to attend.

It is important to note that the fleet was designed and built to assault Alexandria, not Constantinople. The great transports, including the special horse transports, were designed to take advantage of the many sandy beaches in the environs of northern Egypt, where men and horses and machines of war could be placed ashore directly from the ships, and with relative ease. Constantinople had no such beaches available, and had higher towers guarding approaches than any of the towers on the ships. The ships had mangonels and siege weapons and towers aboard which were intended for Alexandria, not Constantinople. The fifty war galleys were built to battle Egypt’s great maritime force; Constantinople had no powerful navy.

The horse transports, in particular, were uniquely designed. They were large but very shallow-draft vessels intended to get very close to beaches to enable blindfolded horses to be led directly out of their stalls and onto the shore. Alexandria had such beaches available; Constantinople did not. The transports had special ramp-equipped water-tight doors built just above the water line to enable loading and unloading of blindfolded horses directly to and from individual stalls below decks. This eliminated the problem of lifting the horses by deck crane and then somehow getting them below decks, and it eliminated the reverse process to unload them. Each stall was equipped with a large belly-strap and winch, which allowed taking much of the horse’s weight off of his feet, preventing him from falling or moving due to ship motion, and keeping cargo weight properly dispersed around the ship. While this was hard on the horses due to immobility and chafing, it was seen to be much better than the older existing alternatives of the day.

The fleet stopped at a number of ports along the coast of Istria and Dalmatia, re-insuring loyalty and support, collecting past-due Venetian tribute and increasing the compliment of rowers and marines from among the populace, who owed Venice military support. Chief among these ports were Pirano, Trieste and Muggia. The fleet arrived before Zara in early November. It was known and recorded before the fleet sailed that it was too late in the season to sail across the Mediterranean to Egypt, since the lateness of the arrival and preparation of the host beyond the contract date was realized. It was known ahead of time that the fleet would winter somewhere this side of the great sea, and so Zara became the intended place to winter.

Politics, Factions, Intrigues and Rationalization regarding the decision to attack Zara and Constantinople.

Now, the predominantly French host, supposedly under the command of the Italian Boniface, who was not present and, conveniently, “tending to other important matters,” was ordered by letter from pope Innocent to not attack any Christian city, and it was clear that if they disobeyed this order they would incur upon themselves excommunication. No formal sentence would need to issue from the See of Rome; the disobedient act itself would bring about the excommunication. From the view of pope Innocent, Boniface was the man in charge; in actual fact, since the crossing of the dodge, it could be argued that this Crusade was now, primarily, a Venetian thing, and that Dandolo was the real man in charge. And Zara was a former Venetian vassal that was in a state of revolt against its suzerain.

So there was really nothing revolutionary about stopping at Zara; it was seen to be within the rights of Venice. To forestall the payment of their severe debt, however, the host had to agree to besiege Zara if she resisted, and that was the real problem.

The biggest single argument in favor of following Dandolo to Zara was the notion that all that might be necessary would be to show up and appear before the city with this great fleet and this great host, and a peaceful settlement would likely be negotiated, without any fighting at all. Of course, the destination of Zara and the intentions toward Zara were kept from the rank and file until the last moment, but all the lords and Nights knew full well what was going on. It looked to be the only way to forestall overdue payment due the Venetians and keep the Crusade itself alive. Still, fighting was not beyond the realm of possibility.

On the one hand, if they incurred excommunication upon themselves, they would not only lose the indulgences and privileges gained when they took the cross, but they would also lose access to the saving grace from any and all the sacraments of the Church, seen at worst as final damnation, and at best as severe hindrance to salvation. Some of the German lords and bishops who’s suzerain was Phillip of Swabia were already under excommunication, and had taken the cross as an act of contrition and penance, hoping to get back into grace with the Church.

On the other hand, if they did not go to Zara, the Crusade itself, as an identifiable entity, was ended. Most of them couldn’t even afford to make their own way to the Levant. They would return home as best they could in disgrace and poverty.

If, for the host, Zara held the promise of forestalled debt, Constantinople held out the promise of debt elimination, and even of enrichment; more on that later.

When Zara saw the approach of the great fleet, she raised her great chain across the entrance to the harbor. One of the fleet’s massive transports ran upon the great chain and broke it, whereupon most of the fleet swarmed into the port. Nights and squires were landed unopposed. The doors of the transports opened, ramps lowered, and the great war horses were led blindfolded to shore. Siege weapons were unloaded and prepared for action. Since they were unopposed, they encamped where they were. Even though they represented only about a third of the contracted-for host, they were still an imposing host, by Western standards or any standards at all, particularly when backed up by all those highly visible ships of war.

The military facts of the matter on the ground at Zara were these. Zara was cut off from all support from anywhere. The Venetians were close to home, on what was essentially a Venetian lake (the Adriatic sea), and were easily resupplied and supported. While Zara had formidable fortifications, the Venetians and the host had time on their side; they had nowhere to go until spring, and more than enough time needed to reduce the city to rubble. These facts were not lost on the Zarans; they knew full well what jeopardy they were in. While they could put up a fearsome resistance for a time, they could not hope to win in the end. Without the ability of their Pisan or Hungarian allies to relieve them, they had no choice but to offer terms.

On November 12, two days after the fleet arrived, a Zaran deputation came to the crimson pavilion of the dodge, Enrico Dandolo, to offer terms of surrender. What they offered was the city and all its goods to be dispensed with at his discretion, with the sole condition that the lives of the inhabitants be spared. The surrender was total.

It was perhaps too rich a moment for Dandolo, and he savored it too long. He had worked and waited long for this moment, and had expended much energy toward it, and now Zara stood at his mercy. He replied that he would need to confer with his French allies before accepting their terms. Which was nonsense, of course; there is no way that the lords would refuse those terms, and Zara was his vassal, not theirs, and the matter should have been settled right then. Dandolo must have wanted the Zaran deputation to spend some time wringing their hands and worrying about survival before he finally gave them their answer. But he waited too long.

The procession of the Zaran deputation to the pavilion of the dodge did not go unnoticed by the Crusading host, and it was clear to all that a surrender was now in progress. For most, this was the best news possible, but there was another faction among them that didn’t appreciate the very idea of being in Zara at all. For them, this news made them angry. Chief among them was Simon de Montfort, one of the first French barons to take the cross back at the tournament at Ecry. He and others among the French had not been happy about the direction of the Crusade since its leadership had been “co-opted” by Italians – first Boniface and now Dandolo – and were certainly not happy to be part of a Christian military force, under the cross, arrayed against the walls of a Christian city. For them, the surrender of Zara was unjust and tragic.

Simon de Montfort and followers visited the Zaran delegation while they awaited Dandolo’s answer, and poisoned the well, as it were. He assured the Zarans of the pope’s support, and that of many of the Crusading host as well. He assured them that none of the host would join the fight if they decided to resist, and their fight would be against the Venetians alone. The host was there for show alone. Reinforcing this message was Robert of Boves, brother of Enguerrand, who rode to the walls of the city to announce to the defenders the same story Simon of Montfort was announcing to the surrender deputation. The deputation thanked Simon for his support and returned to the walls of Zara. So much for an immediate surrender.

Note well that nothing in the pope’s letter forbade the Crusaders from wintering in Zara or from accepting a surrender if freely given. The matter could have been settled peacefully.

Dandolo met with the French lords, and apparently no one noticed that Simon do Montfort and others were not present. Of course, the barons voted and fully agreed to accept the surrender. They then accompanied the dodge to his pavilion to conclude the agreement, where they found no Zarans, but Simon and some of his followers. The dodge and the barons were astonished and angered at what had transpired. Before much of an explanation was offered, a very serious feudal challenge was laid before everyone.

Guy of Vaux-de-Cernay, with the pope’s letter or a copy of it in hand, stepped forward and exclaimed “I forbid you, on behalf of the Pope of Rome, to attack this city, for those within are Christians and you are Crusaders!” and further that to ignore this order would mean excommunication. Violence erupted immediately. Venetians tried to kill Guy on the spot, but his life was saved by Simon de Montfort.

When things calmed down a bit, Enrico Dandolo addressed the Crusading leaders, not the dissidents, saying “Lords, I had this city at my mercy, and your people have deprived me of it; you have promised to assist me to conquer it, and I [now] summon you to do so.”

Which put the lords on the horns of a dilemma. When they could have had a peaceful settlement, now they were re-presented with excommunication on the one hand, and violation of a sworn commitment on the other, along with the death of the rest of the Crusade itself. Everyone was furious at this action instigated by Simon of Montfort.

Many of them never would have agreed to sail to Zara in the first place if the papal legate had not approved it. Now they had the letter before them, and the chance of a surrender was scuttled. More than anything else, it was anger at Simon de Montfort that tipped the scales for the decision to besiege Zara.

What amounted to a truly small and insignificant contingent of dissidents, consisting solely of Simon de Montfort and Enguerrand of Boves and their contingents, moved their encampment to a separate area away from the rest of the host, to not be party to the battle. The Zarans, having taken the word of Simon, refused to believe their own eyes as the host formed up and prepared the weapons of war. The Zarans hung crucifixes from the walls to make it further sacrilegious for Christians to assault them, and watched as the host trenched around the landward sides of the walls and the fleet ships maneuvered close to the seaward side.

It didn’t take too long to come to the shocking conclusion that the Crusading host, unhappy as it was, was determined to reduce Zara and to do it just as quickly as possible. Mangonels, petraries and other engines of war were employed as sappers tunneled undermining the walls to cause them to collapse. The Zarans were unable to thwart the sappers, and their defenses thus far caused few casualties among the host. They soon saw that the situation was hopeless and again offered surrender, again on the sole condition that their lives should be spared. This time it was immediately accepted.

On November 24, the feast of St. Chrysogonus, Zara was occupied, a poverty stricken soldiery was unleashed and the city was put to the sack. Everything of value was plundered, much else was destroyed, and even churches were profaned and looted. The dodge did not honor the terms of the surrender, for many of the city’s leading characters were beheaded, and many more exiled. For the winter, the Venetians occupied the port area of the city, and the Franks occupied the more inland areas.

Much later, perhaps in 1205, the dodge wrote to pope Innocent attempting to justify the conquest of Zara; there is no indication of how that communication was received. He stated that he knew about the papal prohibition, but that he didn’t believe it was a real one at the time. Whatever his relationship with Rome, and whatever the state of his immortal soul, he felt justified in his action for Venice.

Zara was a former Venetian dependency that had revolted; Zaran pirates preyed upon Venetian shipping within the Adriatic; Zarans had even allied with Pisa to challenge their dominion in that area. Venice had made a monumental investment in the Crusade itself, and stood to face a financial catastrophe if the Crusade itself failed or did not pay what was due on the contract. I think you can see that the conquest of Zara was not a simple cut-and-dried story, but was very complex.

Many among the host were concerned about the state of their souls, particularly when subjected to the condemnations of the followers of Simon de Montfort. As a counter to that condemnation, most of the Crusading bishops “absolved” the army of their sin and lifted the ban of excommunication. This was completely uncanonical and ineffective, of course, but it served as a stop-gap effort to sooth the consciences of the soldiery. The leaders did send a delegation of two bishops and two Nights to the pope to explain their situation and seek proper forgiveness. There was no Venetian representative among them, for at that time the Venetians did not admit to the sinfulness of the act.

Early on in the occupation of Zara there erupted violence between the French and the Venetians. Animosities and jealousies ran high on both sides. It got so serious that the lords and Nights actually had to don full armor before venturing into the fray to separate the combatants. As soon as they stopped the fighting in one area of the city, it would break out anew somewhere else. Before it was all quieted down, over a hundred were dead, mostly Venetians. The dodge and the leaders then had to spend considerable time and effort calming the troops and quieting the animosities between the soldiers and the sailors.

Boniface arrived in mid December to find animosity and division between the Venetians and the French, division among the troops, the dissident camp still apart from everyone else, and the quieter but more serious problems among the leaders. The Venetians still needed their payment; it was not eliminated by the action at Zara, merely postponed. The French felt that the Venetians were getting the best of everything and, some suspected, had already been paid more than enough. The dissident faction felt that most of the host had betrayed the Crusader’s vows, and most of the host felt betrayed by the dissidents.

The German envoys from Phillip of Swabia arrived in Zara on the first of January bearing news of the young Byzantine prince Alexius. The arrival was not unexpected by Villehardouin and the other leading barons since they had sent their own envoys to Phillip in support of the imperial hopeful. For the vast majority of the Crusaders, and for the Venetians, the whole story of prince Alexius and his plight came as a complete surprise. The envoys and the barons met with the dodge in an audience in the house the dodge was occupying.

Phillip of Swabia had changed his mind on the matter.

The envoys presented their credentials as legates of Phillip of Swabia and also of prince Alexius. They affirmed Phillips’ desire to send his brother-in-law, prince Alexius, to join the host, and stressed the responsibility of sworn Crusaders to uplift the downtrodden. “Because you march for right, and for justice, you must return the inheritance to those who have been despoiled of it, if you are able.” This was the action that was called for; the envoys then turned to the reward for this service.

- Prince Alexius would place the Greek church in obedience to Rome.

- He would supply the Crusading army and provide them in addition with two hundred thousand marks.

- He himself would raise an army of ten thousand to join in the Crusade for one year.

- Throughout his life he promised to maintain five hundred Nights in the Holy Land.

The German envoys possessed full powers to conclude a treaty on those terms. Of course, as hindsight proves, the young prince Alexius had no comprehension of either the realities on the ground in Constantinople, or of the enormity of the commitment he was making to the great lords. Or, perhaps, he felt desperate enough to promise anything. Desperate men are disposed to promise anything. From the other side, the situation of the great lords was desperate also, and desperate men are likely to grasp at any offered solution that sounds good.

Prince Alexius had grossly over estimated his influence over the Byzantine church. The envoys assured the great lords that the greater part of the population of Constantinople desired the overthrow of the usurper who occupied the throne, and the restoration of Prince Alexius to his rightful rule. This, of course, would prove to be yet another gross over estimation.

The factions weighed the new factors pertaining to the decision to sail to Constantinople rather than Egypt, even as most of the common soldiery still thought they were all bound straight for Jerusalem. The German faction was leery because some of them were already under excommunication because of prior alignment with Phillip of Swabia against Otto, and hoped for exoneration by having taken up the cross and marching for Innocent. However, their position was complicated by the fact that now, their suzerain, Phillip of Swabia, now ordered them to act to place Alexius on the throne at Constantinople.

The Franks were divided, mostly for Constantinople, but some against, led by Simon de Montfort, who saw himself as the champion of papal policy. Some Nights from Champaign who were jealous of the Italian leadership of the Italians from Montferrat and Venice, and of the money Boniface had received from Count Thibaut’s legacy opposed the German proposal and sided with Simon de Montfort. Boniface came down on the side of his suzerain, as did most of the Franks. After some discussion and argument, Dandolo and the Venetians favored supporting Alexius.

Among the clerics, the divisions were similar. Abbot Peter of Locedio followed his lord Boniface, but was terribly troubled because of his attachment to Innocent, and the trust Innocent had placed in him. Abbot Simon Loose was perhaps most prominent in the party favoring Alexius. Abbot Guy of Vaux-de-Cernay, follower of the count of Montfort, was chief spokesman for the clerical foes of the Alexius undertaking. Having already adamantly opposed the attack on Zara, he became even more adamantly representative of the known position of the pope.

The bishops of the host were evenly divided on the issue. The only bishop who strongly opposed the German proposition was Peter, bishop-elect of Bethlehem. The Abbot of Vaux-de-Cernay and his party went farther than most in opposition, insisting that the Crusade proceed at once directly to Jerusalem, and not even entertain the strategy of Egypt first. They forcefully called to mind the Crusader’s vows that they had all taken long ago and which remained unfulfilled.

The one thing that none of them intended – and this is very important – is that not a single noble, Night, cleric or Venetian intended to conquer Constantinople outright. No one in his right mind would have intended such a thing. So far as they knew at the time, that would be a near impossible task, and they were of insufficient force to do it. Constantinople was huge, the fortifications immense and very nearly impregnable, and had stood for centuries against all challengers, and there had been many who had tried and failed. While it may seem terribly naïve today, to our ears, at that time there was no reason to doubt that young Alexius did not have the Byzantine support he claimed to have, or that he could not deliver on any of his promises.

Bottom line: it was a way for the Crusade to continue.

Phillip’s Treaty was eventually signed by the greatest of the barons: Boniface of Montferrat, Baldwin of Flanders, Louis of Blois, Hugh of Saint Pol, and a few others, at another meeting with the German envoys at Dandolo’s temporary lodgings in Zara. They felt they Crusade would be terminated and they would be disgraced if they rejected it. They did this despite the lack of consensus and the open opposition to it among and between the various factions.

Boniface later said that he acted decisively in a desperate situation because the army was out of provisions, and he claimed – falsely – that he was following the advice of the papal legate, Peter Capuano. The signing of the treaty did not put an end to the controversy or the arguments. The Venetians had hoped that the value of the continuance of the Crusade itself would be a significant enough factor to put the matter to rest, but the factions continued to bicker about it.